- This event has passed.

Online Conference | Charles Dickens: Beyond Realism

Charles Dickens: Beyond Realism

17 May, 9.00am-3.30pm British Summer Time (BST)

All sessions are scheduled according to British Summer Time.

Online Conference

Register here.

Dickens’s fiction is celebrated for its vivid realism, luring the reader into the mist and fog of Victorian London’s streets and revealing the profound injustice of day to day life. We find realism in his depictions of place, and his detailed description of characters: it’s certainly a crucial part of his prose. But what are the limitations of his realism, and what can looking beyond its confines tell us about Dickens’s work? Dickens often wrote about the supernatural and invited spirits and ghosts into his stories. His fiction is driven by coincidences and repetition. His sceptical flirtation with spiritualism, his interest in the human mind, in experience, and memory, in the Gothic, and the uncanny or macabre, reveal a ‘shadowy world’, as he puts it in his preface to the 1850 edition of David Copperfield, in which the boundaries between the real and the imagined, the familiar and the feared, are fluidly challenged and explored. Dickens might paint vivid and realistic images of the external world, but they’re accompanied by forays into the mysteries of the internal world of memory and subjectivity. Beyond realism then, Dickens presents a rich world where reality and imagination, the material and the immaterial, past and present, and life and death are intertwined. In many ways, Dickens’s use of non-realist elements is precisely what enables him to create a fictional representation of human existence that is paradoxically more effective and realistic than what strict realism would limit him to.

This symposium, hosted by CNCSI, will feature a series of talks exploring the role, influence and impact of Dickens’s use of non-realist features in his fiction. It will bring together specialists to delineate new trajectories in the study of Dickens’s engagement with non-realism in his work.

Programme

9am BST

Welcome by Emily Vincent (University of Birmingham), Emma Merkling (Durham University)

9.15-10.00 BST

Kirstin Mills (Macquarie University), Dickens and Ghosts from the Nineteenth Century to Now

Chair: Emily Vincent (University of Birmingham)

Abstract

Throughout his life, Charles Dickens was fascinated by ghosts and the claims of Spiritualism. Dickens’s fiction is peppered by ghosts and hauntings of all different kinds and magnitudes and his writing cemented the tradition of the Christmastime ghost story. Privately fascinated by Spiritualism and its quest to scientifically document claims of the afterlife, his public writing is often considered to demonstrate his scepticism towards the possibility of genuine hauntings. Yet Dickens’s treatment of ghosts in his writings is often more ambivalent, playing with questions of psychology and perception to suspend the reader in a state of ambiguous possibility on the brink between reality and unreality. Blending humour and horror, Dickens uses ghosts to probe the human psychological condition, and this is a tradition refreshed and approached anew by contemporary digital adaptations of Dickens’s ghost stories. This paper will explore these contexts to illustrate the centrality of ghosts, the supernatural and non-realism to Dickens’s creative project and the continued afterlives of his tales.

10-10.45 BST

John Bowen (University of York), Dickens’s Theatres of Cruelty

Chair: Jonathan Wild (University of Edinburgh)

Abstract

‘it is understood that life is always someone’s death.’

Antonin Artaud, Letters on Cruelty, First Letter, The Theatre and Its Double

Algernon Swinburne, like many others, saw Dickens as an author of cleanliness and sanity, claiming that the ‘imagination or the genius of Dickens … never condescended or aspired to wallow in metaphysics or in filth’. But Our Mutual Friend positively incites its readers to wallow in metaphysics and filth, although few critical accounts have fully registered the derangement wrought by its embedded cruelties, obsessions and dispossessions to our understanding of Dickens’s work and the nineteenth century novel more generally. In dialogue with Jacques Derrida’s discussion of Artaud’s work in his 1965 essay ‘La parole soufflée’ (1965, collected in Writing and Difference, 1967), I will explore the ways in which Our Mutual Friend is permeated by – and intermittently enacts – strange theatres of cruelty, told through a poetics of articulation and exhaustion whose breath and voices are characteristically derisive, prompted or dead.

10.45-11.00 BST

Break

11.00-11.45 BST

Céleste Callen (University of Edinburgh), Metaphysical Dickens: Time, Memory and Heterogeneity

Chair: Lara Virrey (University of Edinburgh)

Abstract

This research examines the representation of subjective temporal experience in Dickens’s fiction through the lens of Henri Bergson’s philosophy of subjective time. By introducing the flaws in our way of thinking about time, Bergson directly challenges the mistaken attempt to measure time mathematically and spatially, perceiving feelings as external objects, rather than accessing true durée, which felt internally and qualitatively, rather than quantitatively. These notions are already a source of questioning in the nineteenth century and in Dickens’s fiction particularly. Dickens’s fiction anticipates a modern conception of temporal experience, which is rooted in heterogeneity, a coexistence that implies both past and present, memory and re-creation, continuity and change. Through Bergson’s concepts of memory, interconnectedness and continuous re-creation, this paper seeks to reveal Dickens’s ability to shed light on the real, lived experience of temporality.

Dickens creates an in-between world, a metaphysical representation of the lived experience of time that oscillates between memory and reality, between past and present, between the mind and the world. Rather than adhering to the strict confines of realism, Dickens presents a rich world where reality and imagination, the material and the immaterial, the past and present, and life and death are intertwined. Beyond realism then, Dickens’s use of non-realist elements in the Christmas Books represent a turning point that is precisely what enables him to create a fictional representation of human existence that is paradoxically more effective and realistic than what strict realism would limit him to. In his use of narrative voice and the complex double movement between past and present and continuity and change, Dickens provides a heterogeneous representation of temporality. Dickens’s fiction reveals the metaphysical aspect of our subjective experience of time that goes beyond the dualism of mind and matter and complicates the debate between internal/external that was at the heart of the philosophical debates of the time. For Dickens as well as Bergson, it is particularly through the role of memory as a creative force, rather than a static archive, that we can understand the mind and the world as continuously interpenetrating and intertwined in a heterogeneous double movement. I will discuss three of Dickens’s Christmas books, A Christmas Carol, The Chimes and The Haunted Man, as well as two of his first-person narratives, David Copperfield and Great Expectations.

11.45-13.00 BST

Lunch break

13.00-13.45 BST

Chris Louttit (Radboud University), Reading Dickens through the Adaptive Lens of Dystopian Science Fiction

Chair: Amy Coles (University of Buckingham)

Abstract

My talk for the ‘Charles Dickens: Beyond Realism’ Symposium does not focus directly on non-realist elements of Dickens’s fiction itself, but turns instead to two recent adaptations of Oliver Twist (1837-39) which ‘genrify’ Dickens’s novel to adapt and repurpose its characters, narrative and themes to make them resonate for young-adult readers. Adam Dalva, Darin Strauss and Emma Vieceli’s Olivia Twist: Honor Among Thieves (Dark Horse Comics, 2019) and Gary Whitta and Darick Robertson’s Oliver (Image Comics, 2019-20), two roughly contemporary graphic novels, resituate Dickens in the context of dystopian science fiction. This makes sense, according to Darin Strauss, since the grinding poverty and societal oppression represented in Oliver Twist can be read profitably as ‘the original dystopian tale’. The authors of these graphic novels, then, use genre conventions to emphasise a darker interpretation of Dickens. They do so in part, I argue, as a reflection of their own time, and specifically the preoccupations of late-2010s America, at a time when George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) found itself at the top of the bestseller charts and a dystopian mood of what the historian Jill Lepore has labelled ‘radical pessimism’ was in the air. Olivia Twist and Oliver’s reinterpretation of Oliver Twist may well be a strongly politicised one, but, as I will show in my paper, it is also a reworking of the source text that interacts in nuanced ways with more optimistic and hopeful elements of Oliver Twist and its many adaptations.

13.45-14.30 BST

Claire Wood (University of Leicester), Imagining Death

Chair: Amy Waterson (University of Edinburgh)

Abstract

Suppose yourself telling that affecting incident in a letter to a friend. Wouldn’t you describe how you went through the life and stir of the streets and roads, to the sick-room? Wouldn’t you say what kind of room it was, what time of day it was, whether it was sunlight, starlight, or moonlight? Wouldn’t you have a strong impression on your mind of how you were received, when you first met the look of the dying man, what strange contrasts were about you and struck you?

Dickens in a letter to Mrs Brookfield (20 February 1866)

Writing to Jane Octavia Brookfield, a would-be contributor to All the Year Round, Dickens urged her to ‘make more’ of a deathbed scene in her manuscript.[1] Much of his advice centred on the inclusion of realist details, emphasising time, place, and tacit interpersonal dynamics. In many cases, Dickens followed his own counsel. The author penned dozens of deathbeds, among them several that are realist in George Eliot’s sense of the word, emphasising interiority, sympathetic engagement, and the ‘faithful representing of commonplace things’.[2] Death, of course, is both commonplace and extraordinary. In the ‘expressions and looks’ of a dying man, Walter Benjamin reflects, ‘the unforgettable emerges and imparts to everything that concerned him that authority which even the poorest wretch in dying possesses for the living around him’.[3] Dickens makes powerful use of the ordinary/extraordinary fact of death in scenes of commonplace tragedy, such as the demise of Jo in Bleak House, which moves readers to sympathise with the individual and remedy neglect of the many ‘dying thus around us, every day’.[4] But Dickens was not bound to a particular style or mode in his treatment of mortality. Equally powerful, yet radically different in conception, is Oliver Twist’s depiction of the death of a poor woman. Here the horror of the situation is conveyed by lurid, externalised description. ‘It’s as good as a play’ declares the dead woman’s elderly mother, signalling the episode’s melodramatic inheritance.[5]

This paper considers the ‘fusion of realist and anti-realist tendencies’ that shape Dickens’s work, with reference to the ways in which he imagines death in his fiction.[6] In addition to examining the mixed mode of his deathbed scenes, I will explore moments when Dickens goes beyond realism in following the dead as they make their transition into the afterlife.

[1] Charles Dickens, ‘To Mrs Brookfield, 20 February 1866’, The Letters of Charles Dickens: Volume Eleven, 1865-1867, ed. by Graham Storey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999), 160.

[2] George Eliot, Adam Bede, ed. by Valentine Cunningham (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 178.

[3] Walter Benjamin, ‘The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov’, in Illuminations, ed. by Hannah Arendt, trans. by Harry Zorn (London: Pimlico, 1999), 93.

[4] Charles Dickens, Bleak House, ed. by Nicola Bradbury (London: Penguin, 2003), 734.

[5] Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, ed. by Philip Horne (London: Penguin, 2003), 42.

[6] Juliet John, Dickens and Mass Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 196.

14.35- 15.20 BST

Andrew Smith (University of Sheffield), Seeing through the fog: Dickens and the Gothic

Chair: Madeline Potter (University of Edinburgh)

Abstract

Dickens employed the Gothic to address the need for social reform. He achieved this by working beyond realism in order to focus popular attention on the plight of those who are socially and economically isolated. The Christmas ghost stories, which foreground the spectre’s invitation to look at the world differently, provide the clearest example of this (in which Scrooge’s redemption depends upon an alternative way of looking). This issue of sight runs throughout the ghost stories and the journalistic ‘A December Vision’ (1850), but also appears in moments that reflect on crime and guilt. This paper explores representations of seeing and being looked at in narratives which are about fogs, ghosts and prison cell psychologies, which employ images of the haunted self in order to, paradoxically, draw attention to the need for real social and political reform. Texts discussed include the Christmas books, selected journalism, Oliver Twist (1838) and Bleak House (1853).

15.20 BST

Closing Remarks

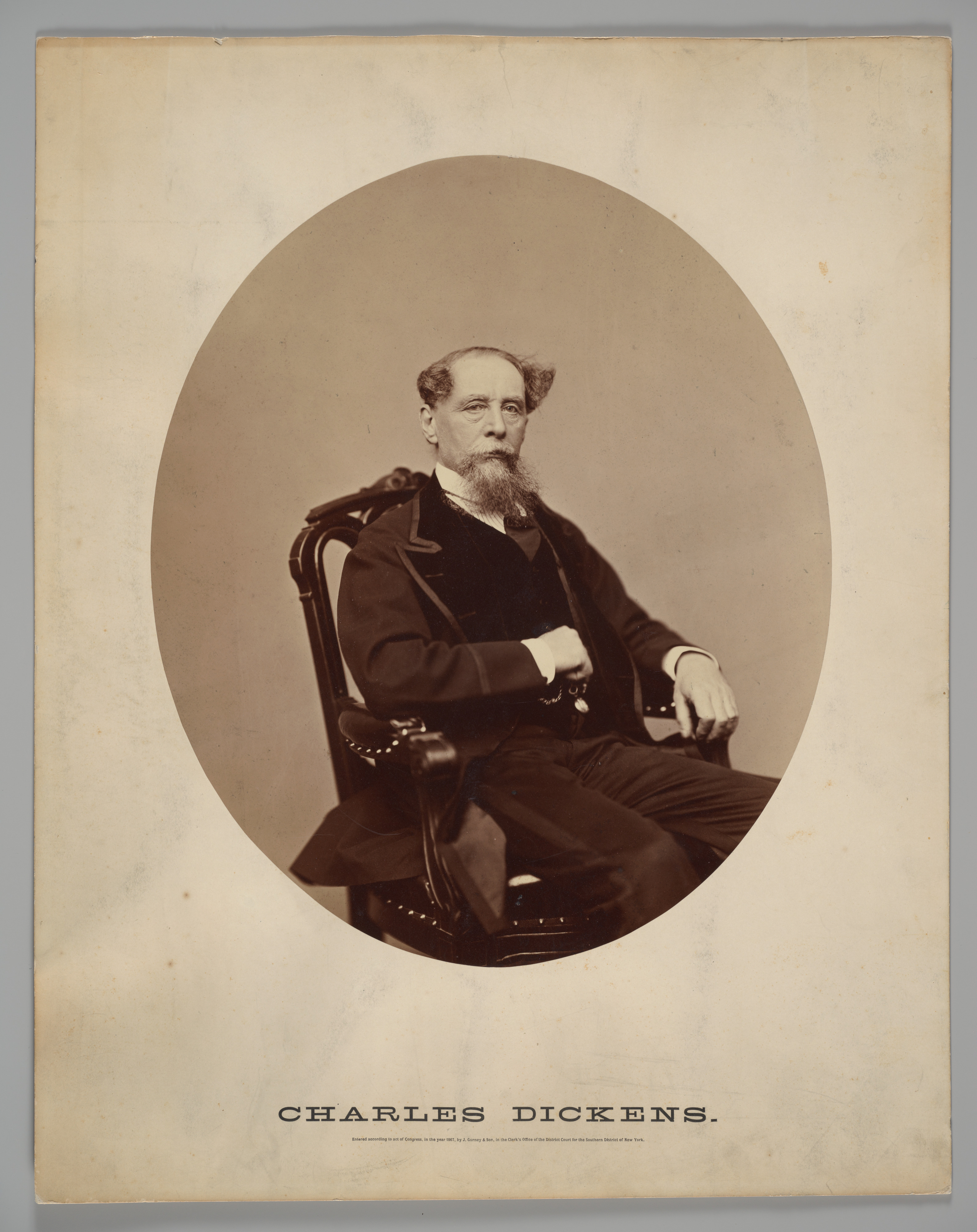

Image: J. Gurney & Son, Charles Dickens, 1867. Open access image curtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.